When I was a kid, I hated history class. To me, it was nothing more than a list of names, dates, and facts about wars and dead people that I was required to memorize. I never saw how it actually applied to my life. But in last few years, I’ve started to LOVE history — largely because I’ve come across amazing stories and nuggets of history that I think are really worth talking about, but which we largely don’t. Some of these stories I’ve found to be especially hopefilled. Since I don’t think these stories get told enough, I wanted to retell some of my favorites. Below is one of them.

Hope you enjoy!

We need to talk about Smallpox. If you’re reading this there’s a decent chance you don’t really know much about it. I didn’t before this past year. I had just kinda assumed it was basically chicken pox, but a bit worse. However, if you had been alive a few centuries ago, you almost definitely knew about Smallpox. You likely would have had a different name for it. But, you definitely would have either heard stories about it, or you would have lived through it.

And you would have, understandably, been horrified of it.

3,000 years of death

Scientists aren’t confident about where or how the Smallpox virus first came to exist. What we do know, however, is that it’s been with humanity for a long time, and it’s killed a LOT of us over the millennia.

The oldest evidence that we have of Smallpox is the mummified remains of an Egyptian Pharaoh who seems to have died from the disease about 3,000 years ago. 1

So, from then on, for a decent chunk of human history, through the rise and fall of several of history’s most powerful empires, Smallpox has been infecting people and making them sick… and killing them…

And what is especially scary to me about Smallpox is just how many people it has killed over the millennia. It can be easy to become complacent when we think about the infectious diseases we face today. Even as we are navigating our way out of a pandemic that has killed millions of people, the percentage of people who died from a COVID-19 infection has actually been comparatively low by historic standards.

Not so with Smallpox.

With Smallpox, the number that tends to be thrown around is about 30%, 2 or around 1 in every 3.

One out of every three people who caught the disease died from it.

One out of every three.

Take a moment to imagine what it would be like if one out of every three people you know who caught COVID had died from it.

Just try to let that idea settle in…

That was a reality for a significant chunk of human history. There was an extremely infectious disease getting passed around across much of human civilization, which would kill nearly a third of everyone who got infected with it (and would leave many of the others who got it with significant permanent damage).

For much of the virus’ history, the only inhabited regions of the world that didn’t have Smallpox was the Americas and Australia. However, when Smallpox finally did get brought over from Europe to those regions (to the Americas in the late 1400s and early 1500s, and to Australia in the late 1700s and early 1800s), it resulted tens of millions of deaths among the indigenous peoples there. 3

Beyond that, it’s estimated that in just the 1900s alone, between 300 million and 500 million people died from Smallpox around the world.4 That’s as much as half a billion, or as much as 13 entire Canadas worth of people who died from the disease!

I realize that’s an inconceivably large number of people to die from something. But, just, try to let the weight of that number settle in.

The word “awful” doesn’t even begin to describe the levels of pain, suffering, and loss that this disease has brought about throughout human history.

If you need a further visual, feel free to take a look at the Wikipedia article for Smallpox, to see some photos of the effects it had on people over the years. But come right back, the story is about to get interesting.

Now, you might be wondering, “If this disease has been so prominent throughout history, why don’t I know anyone who’s gotten it? Why do I know so little about it, if it indeed kills so many people?”

That is a fantastic question.

And to answer it, we need to meet a doctor, some farm-girls, and a cow that changed everything.

Enter: the Bovine

In the late 1700’s, there was a British Doctor named Edward Jenner.

Jenner was a doctor who dealt with and treated Smallpox victims, so he was keenly aware of the damage and loss of life the disease brought about. So he was looking for a way to fight back against it.

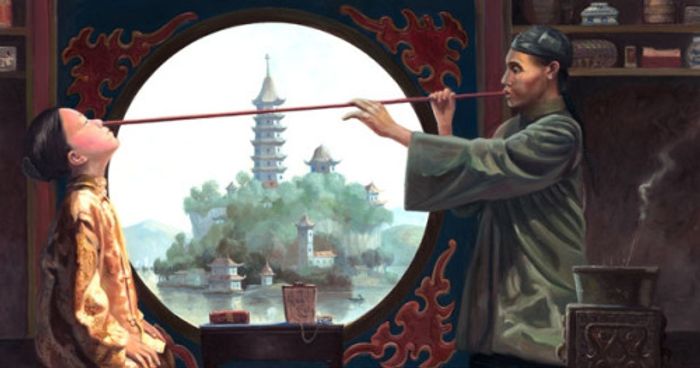

At the time, the most common preventative measure for Smallpox was a process called variolation. The original technique for variolation involved collecting infected Smallpox scabs from patients, drying those scabs, crushing them into a powder, and using a long straw to blow the dried scab powder into the nose and sinuses of the person recieving variolation.

😳

Apparently, history is nothing if not full of terrifying and gross medical treatments.

Here’s the thing, though: around this time in history, variolation (by blowing dried, powdered smallpox scabs into one’s sinuses) was actually the basically best chance you had at preventing Smallpox.5 It did indeed provide half decent protection against the disease. Those who had received the procedure did indeed survive exposure to Smallpox much more regularly than those who didn’t.

But, it was far from enough.

Millions of people were still dying from this disease.

It’s in that context, and in the context of significant outbreaks of Smallpox across Europe and Britain, that our friend Dr. Jenner was working, and researching… and hoping.

Around this time, some other doctors that Dr. Jenner was connected with started noticing something interesting: when a wave of Smallpox would come through an area, there was fairly consistently a group of people that would not die, and many times not even get sick from Smallpox. Sometimes, some of them would get slightly sick. But, consistently, they didn’t die from a disease that was killing large swaths of people around them.

Who was this group?

To the confusion of the medical and scientific communities at the time, it was farm girls!

Specifically, it was the milkmaids who worked with dairy cows.

Which… is a little weird…

Why would milking a cow make you immune to a disease that was killing a third of your town?

The milk wasn’t doing it. Others were drinking milk from these cows and dying.

It wasn’t like beef was the answer. Others were eating cow meat and still dying.

Sooo…. whyyyyy? 🤔

Well, it turns out, many cows in Britain at the time were dealing with a disease caused by a virus that was related to Smallpox, called Cowpox. See, Cowpox is a disease that, while it does infect humans, isn’t lethal to humans. If you were to get infected with Cowpox, in the vast majority of cases, you would simply get a fever, and in some cases, some lesions similar to chickenpox for a few days. Then, after that, you’d recover without issue.

There was effectively no risk of death or permanent damage, which stood in sharp contrast with Smallpox.

And it turned out, these girls who didn’t get sick after being exposed to Smallpox had consistently previously been infected with Cowpox.

This was game changing.

Dr. Jenner theorized that the milkmaids’ specific contact with the pus of Cowpox infected cows had been what gave them immunity to Smallpox.

So, in 1796, Dr. Jenner put that theory to the test. He took a bit of pus from a cow named Blossom, which was infected with Cowpox, and injected it in the arm of a young boy named James Phipps. Little James got a light fever for a few days, then was fine.

Later, when the boy was exposed to Smallpox, he didn’t get sick.

With that success, Dr. Jenner tested his theory again with several more people, by putting Cowpox pus into their arms. Again, when each of those people were later exposed to Smallpox (which, remember, should have otherwise killed nearly 1 out of every 3 of them), they were fine.

Dr. Jenner had just started a process that would change history.

He decided to name this new procedure after the animal that made it possible.

The Latin word for “cow” is “vacca”, from which Dr. Jenner came up with the name for this new process of conferring immunity:

“Vaccination”

Eradicate good times, come-on!

While there were some who resisted, and even mocked the idea of getting immunity to a disease through putting cow pus into one’s body, the evidence was undeniable: without vaccination, Smallpox was still killing about 20-30% of everyone who got infected with it, but with vaccination, that percentage plummeted precipitously.

Dr. Jenner’s vaccination process went mainstream. First dozens, then hundreds, then thousands and beyond started receiving this new vaccination procedure. And as vaccinations increased, Smallpox cases and deaths decreased proportionately.

The process wasn’t completely perfect. A small number of people would still get sick and die from Smallpox after vaccination. 6 And in very rare cases, some people even got very sick and died from the vaccine itself. 7 But still, the result was that exponentially fewer people were getting sick and dying after vaccination, where those who were not yet vaccinated were still dying at a rate of about 1 in 3 from Smallpox.

As time went on, an even more effective and safer vaccine was developed that didn’t require cow pus.

Then, in 1959, the World Health Organization made a goal: they knew that you could stop Smallpox from spreading in a place through vaccination. Large chunks of the Western world were already largely free from Smallpox due to vaccination campaigns in those regions. So, if that was true, then in theory, you should also be able to scale that up.

So, the question was asked, Could you stop Smallpox entirely by vaccinating people in the remaining regions of the world still fighting Smallpox?

Could we entirely eradicate Smallpox?

All the evidence seemed like it was more than possible. And not just possible, but very worth it. The sheer number of lives that had been saved by vaccination was hard to ignore. And the amount of suffering that could stopped by eradicating Smallpox entirely would be almost unimaginable.

So, the World Health Organization made the commitment to do everything within their power to eradicate Smallpox… then they started putting in the work to make it happen.

For two decades, a massive global campaign was rolled out to provide vaccinations to the remaining regions of the world that were still dealing with Smallpox. Hundreds of millions of doses of Smallpox vaccines were produced, distributed, and administered to some of the poorest and most inaccessible regions in the world. This was possibly the largest coordinated public health campaign in history.

Then, in 1977, something amazing happened.

Someone caught Smallpox for the last time.

A Somalian hospital cook named Ali Maow Maalin (who hadn’t been vaccinated against Smallpox)8 caught the disease. Thankfully, he made a full recovery. And because the vast majority of the men and women around him had been vaccinated, none of them caught Smallpox from Ali.

Then, after that, no one caught Smallpox ever again.

Three years after Ali recovered, in 1980, the World Health Organization called it:

Smallpox had been totally eradicated.

Baring a bio-weapon attack, or a lab leak from a lab holding one of the world’s few remaining samples of Smallpox, no one would ever catch Smallpox again.

Since then, over 4 decades have passed, and that’s still holding true — no one has caught Smallpox since.

That’s right. This is a true story from history that actually ends with "… and they all lived happily ever after."

Or, at least, "… and they all lived Smallpox-free ever after," which, all things considered, is fairly close.

“Smallpox was…”

The first two words of the Wikipedia article for Smallpox make me regularly ponder:

Smallpox was…

It’s been thousands of years that humanity and society has been dealing with and succumbing to this devastating disease. Through all that time, how many people wished that this disease would stop? How many people hoped beyond hope that their village or their family wouldn’t have to deal with the tornado of death that tore through communities during Smallpox outbreaks?

And how many times did people think, “This is just the way things are, and this is the way they will always be”?

Here’s the thing: We now know that last sentiment is a lie.

The way things are doesn’t have to be the way things will be.

Only a few short decades ago, people were dying by the hundreds of millions from a millennia old disease that we could barely imagine a world without…

And yet, today, that disease is completely gone.

It makes me wonder, what other travesties and sources of human suffering do we take for granted because we’ve never known a time in history without them?

History shows us that there are terrible things in the world that we can get used to as just “normal parts of life”, but which can be eliminated. Things which our children and grandchildren may not even know a name for, because they never experienced the suffering that those before them dealt with for thousands and thousands of years.

The story of Smallpox reminds me to hold on to hope, even for the things that many people think are impossible.

It reminds me that there are big, bad things in this world that we take for granted.

But that no matter how big or how bad those things might be, a world without that suffering is possible. And, I think, a world like that is worth pursuing.

Smallpox was…

In the eyes of history, Smallpox is counted as a “was”.

What other things have we gotten used to, that deserve to be a “was” of history, too?

-

https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/smallpox_01.shtml ↩︎

-

https://www.pbs.org/gunsgermssteel/variables/smallpox.html ↩︎

-

D. A. Henderson. (2009). Smallpox: The Death of a Disease – The Inside Story of Eradicating a Worldwide Killer. Prometheus Books. ↩︎

-

Actually, that’s not completely true. The variolation process of had evolved a bit by Dr. Jenner’s time. The Ottomans in Istanbul had discovered you could actually get a protective effect similar to the scab-powder-in-sinuses method by making a small cut in a patient’s arm, and putting the same scab powder into their body through that cut. Still nasty, but thankfully no need to stick a straw up your nose. ↩︎

-

Discussion about the “modern” version of the Smallpox vaccine; similar principle, but different numbers would be applicable for Jenner’s vaccine: https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/vaccine-basics/index.html ↩︎

-

Again, an article applicable to the modern Smallpox vaccine and safety: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-most-dangerous-vaccine/ ↩︎

-

Ali was quoted by the Boston Globe in 2006 saying, “I was scared of being vaccinated then. It looked like the shot hurt. Now when I meet parents who refuse to give their children the polio vaccine, I tell them my story. I tell them how important these vaccines are. I tell them not to do something foolish like me.”

Original article: https://web.archive.org/web/20160206111757/http://www.boston.com/yourlife/health/diseases/articles/2006/02/27/polio_a_fight_in_a_lawless_land/ ↩︎